The very interesting social-media curation tool Storify was released in private beta on Tuesday at TechCrunch’s Disrupt conference. It neatly twists the idea behind Flipboard.

Flipboard automatically generates a list of stories that might interest you, based on links suggested by people you follow on Twitter or your Facebook friends. Storify reverses the flow – it allows you to easily curate a list of readings you recommend, based on your own (or others’) social-media postings.

It’s still early-release stuff – the UI, while clean, is a bit obscure (especially the flow to save, then edit, a Storify “story.”) And, like all new tools, it’ll take a few weeks for the collective “us” to figure out how to best use it. But it’s a neat mashup of technology and journalism, and it’s worth watching.

Why? Tools like this are part of the emerging news ecosystem – how can we tap the experts out there to surface smart stories on important niche topics? It’s a problem – and opportunity – my skunk-works team at PBS is thinking about a lot.

A sample – which I ginned up in all of three minutes based on the intertwined riffs of newspaper brain drains and the reinvention of what Washington journalism can be:

OK, so a raw feed of pertinent tweets isn’t a “story” in a traditional sense. But marry this with a quick text introduction (which I, um, was a bit too lazy to write) and you’ve got the makings of useful information.

A side note: The smart folks at Storify deserve all the kudos. But I’ll point out that my friends at the Knight Fellowships at Stanford can claim godparent status: co-founder Burt Herman spent the last year as a Knight Fellow, thinking about ways to use technology to reinvent journalism.)

And a big hat-tip to MediaBug‘s Scott Rosenberg for the blog post that tipped me to Storify.

Eleven years ago, I caught the break of my life: I got a one-year Knight Fellowship at Stanford. (I still find it so shocking that I rarely mention it. Friends say it usually takes at least 18 seconds before I bring it up in conversation.)

I’m unabashed about how grateful I am to the program – whatever I’ve achieved in the past 10 years of my career is due solely to what I learned on that fellowship.  Jim Bettinger and Dawn Garcia are to be commended for dramatically shifting the program’s focus to address the radical changes facing our industry.

Until two years ago, the program operated much like the Nieman Fellowships at Harvard, or the Knight-Wallace program at Michigan: Pitch us an idea that will make you a better journalist. It might be Internet economics (my topic); it might be studying the narrative form of American musical theater.

Stanford has unique qualities, however – it’s a world-class university in the heart of Silicon Valley, a place that has consistently spawned great companies. Now the Knight program asks applicants to submit ideas that “focus on innovation, entrepreneurship and leadership to foster high quality journalism during a time of profound transformation.â€

For several years, I’ve gotten to peek at the stack of ideas as one of several former fellows who help the program staff screen applications (nearly 150 U.S. applications for the 2010-11 class). We completed that initial screening last week. There’s still a lengthy process of interviews and review by the program committee before next year’s fellows are announced in April.

Still, there are several useful lessons in this year’s stack, applicable not only to future Knights, but to anyone who aspires to entrepreneurial journalism. (All opinions are my own, of course, not those of the program.):

What was great:

-  A “just do it†attitude: Personally, I loved the people whose proposals (and, usually, their current work) showed a bias to action. They launch stuff knowing it isn’t perfect, then adjust based on the audience reaction. That’s a far cry from the attitude most of us developed in the days of monopoly outlets. (I remember an editor screaming at us we should never experiment on our readers. Sounds reasonable – but in practice, it meants we never tried anything new.) A thousand start-ups are experimenting out there – and an axiom of the startup world is that with enough experiments, someone will figure out what works.

- Awareness of the trends in technology. You don’t need to be a technologist to get a fellowship – but it sure helps to know broad trends in technology, especially as they affect journalism. The best applicants understood that cheap tech gives anyone the ability to publish; and that it’s getting easier by the day to organize and display vast pools of raw data.

- It’s not just about the World Wide Web anymore. (Doesn’t the very phrase “World Wide Web†sound archaic?) Several applicants noted that publishers need to deliver information when, where and how consumers want it – and increasingly, that means mobile devices. The best name-checked the iPad specifically.

- Recognition that Stanford is a candy store of knowledge. The best went out of their way to discover the particular professors, classes and research going on at Stanford related to the applicant’s idea. (Hint: If you’re thinking of applying for a fellowship anywhere in the future, write that one down.)

What wasn’t so great:

- Applicants who focused their proposals on “saving newspapers as we know them,†rather than saving journalism. There’s a difference.

- Those who acted as if the fellowship is a lifetime achievement award: “I’ve done this and this and this – so someone somewhere owes me a sabbatical.â€

- A corollary: “I need a year off to learn all this new, foreign digital stuff.†Stanford is a marvelous place to learn about the interplay of technology and storytelling – but basic knowledge can be acquired anywhere. Start with the people on the digital side of your current or former shop. And don’t make the mistake of implying that they’re not journalists because they sometimes hold different opinions than you. (Someone did that in a fellowship application a year ago. Guess what? They didn’t get a fellowship.)

- “At the end of the year, I’ll have produced a report.†To steal a line from my former colleague Chris Krewson: The future of journalism isn’t going to be invented at a conference. Studies are helpful, of course – but only when they lead to actual publications that can be tested in the marketplace.

Best of luck to the Knight class of 2011. I’m insanely jealous of you all.

A snarky comment on Alan Mutter’s blog set me off the other day. Alan was reacting to Mark Potts’ excellent riff on the coming iSlate (not just a fanboi dream, but potentially a great leap forward). Predictably, some of the commenters were pining for 1994:

“This smells a little like Google, which siphoned off $21 billion a year from newspapers without a squawk until publishers woke up.â€

We’ll leave aside the petty detail ($21 billion, yes. From newspapers? Um, no.) to focus on the bigger point. The real culprit in the Great Mass Media Collapse isn’t Google. It isn’t Craig Newmark. It isn’t the Original Sin of Not Charging for Content in 1994. (Alan, we tried. Remember AOL and Digital Cities?)

The real culprit? Gordon Moore.

The hero of our story

What, my journalistic brethren? You can’t quite recall studying him along with John Peter Zenger*, Thomas Jefferson & Woodstein back in J-school?

That’s because you almost certainly didn’t – but you almost certainly should now.

Moore, the co-founder and former chairman of Intel, observed in a 1965 trade-magazine article that the power of computing devices was doubling every two years. The importance wasn’t that electrical engineers could cram more circuits onto a chip – but that in doing so, the cost of computing would fall proportionately.

He theorized that the trend would continue indefinitely. Nearly 45 years later, it still holds – so much so that it isn’t called Moore’s theory, it’s called Moore’s Law. To a technologist, Moore’s Law is what the First Amendment is to us.

Want to know why you can get a DVD player for 29 bucks? Moore’s Law. Want to know how your cellphone has become so complicated you need a 15-year-old to explain it? Moore’s Law.

Want to know why newspapers are collapsing, or why local broadcast stations are becoming little more than a transmitter stick in an empty field? Then stop griping for a moment, and understand Moore’s Law.

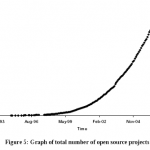

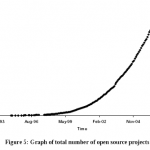

Exponential equations (doubling every two years) are tricky things to wrap your mind around. It’s not a straight line on a normal graph – it’s a hockey stick (or the right half of a parabola, to get all precise about it). To really get a feel for the numbers, you need to play with them.

The Official Chart of Silicon Valley

Dell.com has a spiffy, reasonably functional desktop computer this morning for less than $300. It runs at a speed – does things, in other words – that would have cost $600 in 2007, $1,200 in 2005.

OK, you say, got it: computers get better over time. But do you really get it? Keep going: The same performance would have cost nearly $20,000 10 years ago, at the height of the digital bubble. Not so long before that, when I was studying Zenger, Jefferson et al (and playing poker all night) in college, that much computing power would have cost nearly $5 million.

Here’s how that is “killing†newspapers: Let’s say you had an idea back at the top of the bubble in 1999 – a niche site for a community without a newspaper, or a portal of all the opinion pieces relevant to your city. You’d bring in a technology partner for a consultation. He says, “It’ll cost you a million bucks.†You’d probably gulp, and walk away. And, years later, you’d still be thinking “I can’t do that idea because it’ll cost a million bucks.â€

Meanwhile, some kid who understands Mr. Moore’s relentless math is chasing after that idea for under $30,000.

Therein are the roots of the woes affecting Old Media.

Our audience now has endless choices of news and information because you don’t need a $120 million printing press or a $50 million TV license anymore to publish. As Jay Rosen noted nearly four years ago, the people formerly known as the audience are now collaborators and potential competitors.

For the same reasons, our advertisers have the same sort of cheaper options. The local restaurant that used to buy a 2×5 coupon ad every week? Publishing their own coupons online, and laying our zero cash for a marketing program from Groupon. The car dealer? Using cars.com and AutoTrader for about $2,500 a month combined instead of buying a full-page ad for $10,000 a week.

Blaming Craigslist isn’t going to change those facts. Neither is blocking Google from crawling your site. (Notice how Rupert is screaming – but hasn’t actually blocked robots.txt yet?)

But “stop blaming the wrong people†is only half my intended message.

Why did we bother to study Zenger and Jefferson? Why are they considered heroes centuries later? Because of their spirits of daring, the possibilities they opened for us.

We should understand Moore’s Law now for precisely the same reasons. Yes, it has been a gigantic sledgehammer that has shattered the underlying business models of mass media, and it isn’t going to be repealed any time soon.

It also helps to remember that hammers are used to build things, too.

Instead of looking back, face the other direction. Pick up the hammer, and start thinking about what you can do with it.

Certainly that’s what my work is about these days. But I’ll pontificate some more about what kinds of things you can do with the hammer in a couple of days.

(*Colonial-era printer. Pissed off the governor of New York by daring to print criticism. Charged with seditious libel. Got off with the novel idea that truth is a defense. See, Bill Francois , I was paying attention.)

, I was paying attention.)