Entries Tagged 'Media economics' ↓

April 27th, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics

Most of what I hate about the newspaper industry was encapsulated in a single session at the American Society of News (not Newspapers! Really!) Editors meeting in D.C. a few days ago. An otherwise smart agenda took the inevitable detour down the rabbit hole with yet another discussion of pay walls.

Walter Hussman, publisher of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in Little Rock, flogged his usual paywall-as-a-defense argument: In a world where online users are worth less than print readers, he seems to say don’t bother with the former. “Why would I want to be platform agnostic when I can get (ad rates of) $40 (per thousand print readers) instead of $4?â€

I was reminded of two recent, similar quotes:

-  An analysis ascribed to Washington Post president Steven Hills in a devastating New Republic piece on the paper’s woes: Post print readers are worth $500 a year in revenue; online readers are worth only $6.

- Rupert Murdoch’s assertion that users will cough up for online content: “When they’ve got nowhere else to go they’ll start paying.â€Â Â

Hussman and Hills are both falling for the same “defense first!†mentality that has crippled innovation at newspapers. They’re implicitly assume print readership will stay the same forever (it isn’t ), and that print ad revenues will maintain, too (they aren’t).

Rupert is making an even bigger mistake. He assumes “nowhere else to go,†conveniently forgetting that his media empire was built on expensive printing plants and government broadcast licenses, each of which makes competition economically unfeasible.

Clearly, Rupe hasn’t noticed that those monopolies are gone (or maybe he’s blustering). Local television stations are emerging as real competitors to newspaper sites in many markets. Some, like Allbritton Communications in Washington, are building separate sites to target niches and general news. And there are plenty of independent local  sites, with new ones springing up all the time. On their own, they may not seem formidable. But enough of them in a community could ruin a local newspaper publisher’s day. No wonder potential entrepreneurs are licking their chops.

(The ease of publishing via free services like WordPress  and Blogger are a key reason that “information wants to be free.†More on that, including some semi-geeky economic theory, another day.)

If competition makes paywalls nothing more than defense (and the numbers sure seem to make that case), then what’s a better answer? What gets at Hussman and Hills’ arguments that print readers are worth more?

Let’s take this out of the emotional world of change for a second, and into the dispassionate world of math. Everyone remember the commutative and associative properties from third grade?

If your print readers are worth 10 times your online users, then work to get 10 times the number of online users. You’ll make the same amount of money. (Actually, you’ll end up with more – production costs are lower on digital platforms. No paper, no trucks.)

Daunting? Sure. Simply regurgitating your print product in digital formats won’t grow your audience ten times. No single product will, either.

But a network of niche products is part of the answer.

So is good app for the iPad (and don’t forget the waves of similar devices that are sure to follow).

It also means forcing the business side of the house to think clearly and execute. And it means engaging in biz-side thinking ourselves.

If our goal is to grow our audiences again – not merely milk the ones we have – we have to engage consumers. We have to give them what they want, when, where and how they want it.

Yes, it’s not easy. Innovation never is.

But doing nothing – or hiding behind a paywall – merely guarantees a slow, lingering death for newspapers. That’s unfair to shareholders, to employees – and ultimately to the communities we serve.

April 3rd, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics, Technology and media

Matt Mullenweg is at it again.

He’s the creator of WordPress, one of the free tools that’s reinventing the world of media and the very definition of what it means to be a “journalist.â€

How does Mullenweg justify giving away the results of years of work? Then working more untold hours on upgrades (helllll-ooooo Version 3!)? Then giving it away, too?

Simple: He builds complementary businesses that play in the WordPress eco-system.

You can set up your blog at WordPress.com for free. Want extra features – like truly massive amounts of storage for video, or a custom domain name? Pay a few bucks a year.

His company, Automattic, does other things, too. It provides hosting services for high-volume blogs. It builds paid add-ons for sites, like poll/ratings widgets. His latest is a service that makes it easy to create backups for WordPress sites – especially people who run large blog networks – for less than $20 a month.

None of these fees are large themselves, but they add up.

There’s a lesson there for journopreneurs:  Don’t get embroiled in the endless, economically unviable wishful thinking about paid content on the web. Relent and give the content away – then figure out how to make money elsewhere in the ecosystem.

That could be slick, intuitive and innovative delivery mechanisms – especially on tablets and mobile devices.

It could be building real communities around topic pages, comments and local blog networks, and serving as a sales-and-servicing agent for them. Or banding that community together for group-buying experiences.

Or – and this is the fun, scary part – it could be an idea that no one has figured out yet. One of just might.

(This is why one of my icons at Gravatar – another of Mullenweb’s companies – is a mad scientist. A small prize, and an AARP card, to the commenter who first identifies him. ;-) ).

(This is why one of my icons at Gravatar – another of Mullenweb’s companies – is a mad scientist. A small prize, and an AARP card, to the commenter who first identifies him. ;-) ).

March 18th, 2010 — Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics, Technology and media

OK, I know that I rant about Moore’s Law continually. It’s the key driver of the digital age. It’s why things that seem incomprehensible get invented, and it’s why things that flopped spectacularly just a few years ago are common and successful today.

But many people – traditional journalists especially – struggle to get Moore’s Law. “Half as expensive per unit of computing power every 24 months … wha?!?â€

This analogy struck me today (and, thanks, Florida, for blowing my bracket on the very first afternoon): The NCAA tournament is an example of a Moore’s Law function in action. How do you get from 64 teams to the Sweet Sixteen in just four days? Simple: The number of teams drops by half every round.

The tournament grinds down 64 teams to the final four in just eight game days.

Moore’s Law grinds down a $500,000 server to under $10,000 in a decade.

Don’t let the math equations freak you. Just know that whatever kind of entrepreneurial journalism you want to try, the hardware is cheap. And it will only get cheaper. (The software, too.)

Fear the Turtle.

March 9th, 2010 — Business of news, Media economics

Hal Varian – brilliant economist, one of the few to apply the discipline to information, and all-round nice guy — got off a terrific blog post  at Google today.

I’d love to write extensively on it. But, as usual, Hal expresses his ideas far better than my pea brain can. In about 1,100 words, he manages to explain why paid content probably won’t work for most news sites; remind newsies that Google isn’t the enemy; and exhort news organizations to “experiment, experiment, experiment†for the civic good.

I know this won’t stop the incessant whinging from some quarters, or end the drumbeat of self-referential and circular thinking: “My work has value! Therefore someone should pay for it! So throw up a pay wall! Because my work has value!â€

For anyone willing to explore these topics with cool detachment, a couple more facts to give Hal’s work more weight. His Information Rules, written with Scott Shapiro, is a seminal book in the field of information economics (I’ve given away several dozen copies over the years, and it’s Book No. 1 in my personal essential bibliography of information economics). And odds are if you studied microeconomics in college, you read Hal’s work there, too.

Dismiss him as some sort of biased Googler at your own peril. This is one of the finest economic minds of our age.

A side note: I’ve heard some grumbling already about Hal’s assertion that very few advertisers are attracted to hard news.

I’ll go him one better, based on too many years of sitting in Monday-morning meetings where the previous week’s ad lineage results were discussed: About the only advertisers who insisted on being close to the hard news – in the A section, as far front as possible – were major regional and national advertisers like the department stores and cell-phone companies. Some wouldn’t even pay for the ad if they were bumped back to the Local section.

The rest of the advertisers? They didn’t care, or wanted to be far away from the news:

– Car ads (buried in the back of the classifieds sections, generally)

– Real estate ads (ever notice that they’re not in the Sunday real-estate or home section? Realtors hate news that isn’t “everything’s great! Buy a house!â€)

– Help-wanted ads

– Sunday free-standing inserts, tucked in the comics or some other pre-printed section

– Zoned retail ads in the Neighbors or hyperlocal sections

At most newspapers, those categories easily comprised 60 percent or more of advertising revenues in the halcyon days. Think about that: The majority of the money didn’t want to be near the news; they simply wanted the newspaper as a convenient delivery package.

February 17th, 2010 — Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics

I had a quick conversation the other day with someone interested in using my colleagues at GrowthSpur to help launch his news web site. As usual, I encouraged him to charge ahead – but urged him to pick a niche, not launch a general news web site.

This goes against years of training and experience most of us have as traditional journalists: Bigger is better, right? Cover more things, get a bigger audience?

It’s hard sometimes to pull ourselves away from topics we know too well. So to understand why niche sites work so well, let’s look instead at the same issue in another industry – retailing.

Sears' logo, circa 1970

In the middle of 20th Century, Sears was the dominant store in America. It offered most things to most people, conveniently located at almost every mall in America. Their shirts weren’t the greatest, but they had a plentiful selection. Downstairs, the hardware department had most of the tools you’d need; out in the garage, you could get a new Die-Hard and fresh tires.

Today, Sears is a mere shadow of itself – and it wasn’t dethroned by Montgomery Ward or others who tried to do the same thing, just better. Continue reading →

February 4th, 2010 — Business of news, Media economics, Technology and media

Note: My friend and former colleague Bill Day is one of the sharpest sales-side guys I ever worked with. He’s adept at dealing with traditional, agency-driven advertisers and their massive buys – and maybe even better at bundling together innovative ideas like events, direct marketing and promotions to tap revenue from people who rarely advertise with local media. Bill has sold and serviced tens of millions of dollars in print ads – and quite a bit of online revenue for me, too.

He offers this guest post, from his seller’s perspective, on the publishing-industry frenzy over Apple’s iPad.

By Bill Day

Much is being made of the iPad as a vote of confidence from Apple for traditional publishers like The New York Times. Boosters point to the resurrection of the music industry on the backs of iTunes and the iPod. They predict a similar resurrection for publishers with the pending release of the iPad.Â

Poynter has an interesting take on the potential impact of the iPad on publisher subscription models here. It’s kind of like the cell phone loss-leader model – giving away flashy tech toys for long-term subscription revenue. It’s not a terrible idea. It just misses the point.Â

What’s lost in these discussions is a firm grasp of the mechanics of revenue generation for old-line media. As in “what’s the advertising model?†Continue reading →

January 28th, 2010 — Business of news, Media economics

Much kerfuffle – and more derision than warranted – erupted earlier this week when the New York Observer reported that Newsday has sold only 35 online-access subscriptions since it walled off the site last October.

There was astonishment at the low numbers:

“Michael Amon, a social services reporter, asked for clarification. “I heard you say 35 people,” he said, from Newsday‘s auditorium in Melville. “Is that number correct?” [Publisher Terry] Jimenez nodded.

There was hand-wringing: The Observer’s John Koblin archly observed that Newsday.com’s relaunch and redesign last year cost $4 million … to gross $9,000 in revenue.

That analysis is technically correct, and utterly wrong. Ultimately, that’s why neither side in the Great Paywall Religious War should waste any time thinking about it.

Newsday’s pay wall isn’t about making online-subscription revenue. It’s only partially an attempt to protect print circulation. It’s all about protecting one of the most lucrative businesses around – high-speed Internet access.

The paywall rules first: The only people who get unfettered access to newsday.com are Newsday print subscribers (there’s the modest defense for print circ) and/or subscribers to the Optimum Online high-speed Internet service provided by Cablevision, Newsday’s owner.

Let’s do the math that the Observer, the grumblers in the Newsday newsroom, and just about every blogger out there didn’t bother to do. (I was hoping Alan Mutter would do it for me – lord knows he’s great at it – but he was writing about the iPad today.)

First, understand the economics of the cable-television business: Most of the costs are in stringing the wire past your house. (Lump in the copper or fiber itself, the equipment back at the cable headend and the labor to keep it all running.)

Depending on how tightly houses are packed, it all can run from a few hundred to as much as $1,500 “per household passed†in cable slang.

Oh – Cablevision pays that whether you subscribe or not. Every neighborhood they try to serve is a massive sunk cost.

Now let’s look at the revenue side of the cable business: A subscriber in my wife’s ancestral homeland of Massapequa might pay $50 a month for basic cable. But Cablevision has to share that revenue with the programmers – a few pennies per month per subscriber for niche channels like National Geographic, but more than $3 a month for behemoths like ESPN. Basic cable is a nice business, but not an obscene one.

The obscene ones are those the cable companies entered in the last decade: digital telephone service, and high-speed Internet. They had to upgrade their wiring – and for a company like Cablevision, that meant shelling out billions. But once they did, they could offer bundles of service with essentially zero added cost.

Think about that for a second: They already paid for the wires past your house. If they can get you to sign up, they collect $30 to $40 a month for high-speed Internet. Their cost? A few pennies in FCC fees (oh, wait – they add those onto your bill!), a few more pennies to print the bill (oh, wait – they’re bribing you to “go green!â€), maybe 40 bucks once for the cable modem (that’s why they give it to you!).

Let’s round it down and say that every Cablevision high-speed customer is worth $400 a year in profit.

That’s a fabulous business. Until, say, Verizon FiOS comes to town with a competitive product.

So the math gets really simple: If FiOs can convince a mere 100,000 people on Long Island to switch, Cablevision loses $40 million a year in profits.

If you’re Cablevision, you use every tool at your disposal to stop that. Even the blunt cudgel of a pay wall at Newsday.

I have no particular love for the spinmeisters at Cablevision, but the math backs up their words: the paywall strategy at Newsday is designed “to provide Cablevision’s high-speed Internet customers with reasons to remain with Cablevision, reasons to return to Cablevision, or reasons to choose Cablevision.â€

January 18th, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics

A snarky comment on Alan Mutter’s blog set me off the other day. Alan was reacting to Mark Potts’ excellent riff on the coming iSlate (not just a fanboi dream, but potentially a great leap forward). Predictably, some of the commenters were pining for 1994:

“This smells a little like Google, which siphoned off $21 billion a year from newspapers without a squawk until publishers woke up.â€

We’ll leave aside the petty detail ($21 billion, yes. From newspapers? Um, no.) to focus on the bigger point. The real culprit in the Great Mass Media Collapse isn’t Google. It isn’t Craig Newmark. It isn’t the Original Sin of Not Charging for Content in 1994. (Alan, we tried. Remember AOL and Digital Cities?)

The real culprit? Gordon Moore.

The hero of our story

What, my journalistic brethren? You can’t quite recall studying him along with John Peter Zenger*, Thomas Jefferson & Woodstein back in J-school?

That’s because you almost certainly didn’t – but you almost certainly should now.

Moore, the co-founder and former chairman of Intel, observed in a 1965 trade-magazine article that the power of computing devices was doubling every two years. The importance wasn’t that electrical engineers could cram more circuits onto a chip – but that in doing so, the cost of computing would fall proportionately.

He theorized that the trend would continue indefinitely. Nearly 45 years later, it still holds – so much so that it isn’t called Moore’s theory, it’s called Moore’s Law. To a technologist, Moore’s Law is what the First Amendment is to us.

Want to know why you can get a DVD player for 29 bucks? Moore’s Law. Want to know how your cellphone has become so complicated you need a 15-year-old to explain it? Moore’s Law.

Want to know why newspapers are collapsing, or why local broadcast stations are becoming little more than a transmitter stick in an empty field? Then stop griping for a moment, and understand Moore’s Law.

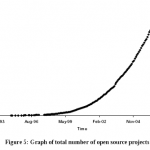

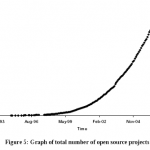

Exponential equations (doubling every two years) are tricky things to wrap your mind around. It’s not a straight line on a normal graph – it’s a hockey stick (or the right half of a parabola, to get all precise about it). To really get a feel for the numbers, you need to play with them.

The Official Chart of Silicon Valley

Dell.com has a spiffy, reasonably functional desktop computer this morning for less than $300. It runs at a speed – does things, in other words – that would have cost $600 in 2007, $1,200 in 2005.

OK, you say, got it: computers get better over time. But do you really get it? Keep going: The same performance would have cost nearly $20,000 10 years ago, at the height of the digital bubble. Not so long before that, when I was studying Zenger, Jefferson et al (and playing poker all night) in college, that much computing power would have cost nearly $5 million.

Here’s how that is “killing†newspapers: Let’s say you had an idea back at the top of the bubble in 1999 – a niche site for a community without a newspaper, or a portal of all the opinion pieces relevant to your city. You’d bring in a technology partner for a consultation. He says, “It’ll cost you a million bucks.†You’d probably gulp, and walk away. And, years later, you’d still be thinking “I can’t do that idea because it’ll cost a million bucks.â€

Meanwhile, some kid who understands Mr. Moore’s relentless math is chasing after that idea for under $30,000.

Therein are the roots of the woes affecting Old Media.

Our audience now has endless choices of news and information because you don’t need a $120 million printing press or a $50 million TV license anymore to publish. As Jay Rosen noted nearly four years ago, the people formerly known as the audience are now collaborators and potential competitors.

For the same reasons, our advertisers have the same sort of cheaper options. The local restaurant that used to buy a 2×5 coupon ad every week? Publishing their own coupons online, and laying our zero cash for a marketing program from Groupon. The car dealer? Using cars.com and AutoTrader for about $2,500 a month combined instead of buying a full-page ad for $10,000 a week.

Blaming Craigslist isn’t going to change those facts. Neither is blocking Google from crawling your site. (Notice how Rupert is screaming – but hasn’t actually blocked robots.txt yet?)

But “stop blaming the wrong people†is only half my intended message.

Why did we bother to study Zenger and Jefferson? Why are they considered heroes centuries later? Because of their spirits of daring, the possibilities they opened for us.

We should understand Moore’s Law now for precisely the same reasons. Yes, it has been a gigantic sledgehammer that has shattered the underlying business models of mass media, and it isn’t going to be repealed any time soon.

It also helps to remember that hammers are used to build things, too.

Instead of looking back, face the other direction. Pick up the hammer, and start thinking about what you can do with it.

Certainly that’s what my work is about these days. But I’ll pontificate some more about what kinds of things you can do with the hammer in a couple of days.

(*Colonial-era printer. Pissed off the governor of New York by daring to print criticism. Charged with seditious libel. Got off with the novel idea that truth is a defense. See, Bill Francois , I was paying attention.)

, I was paying attention.)

January 4th, 2010 — Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics

My older brother used to joke that when I wanted to learn to play baseball, I read a book. Mike’s style: Pick up the ball and throw it harder than seemed humanly possible.

Hey, we all learn differently, right? So when friends – especially newsroom lifers – ask how they can catch up with the digital revolution, I default to books. These are some of the titles that formed my thinking about information economics and the digital revolution.

Read these and you’ll understand that “information wants to be free†isn’t religious sloganeering – it’s the logical outcome of perfect, free copies. You’ll also understand how that same force Continue reading →

January 3rd, 2010 — Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics

Like an awful lot of Americans, I spent the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day gorging on filmed entertainment. In between fistfuls of unhealthy popcorn, I started to think about the lessons two of the movies can teach entrepreneurial journalists.

The first: Avatar, in all its 3D glory at the local cineplex. James Cameron spent at least $230 million – and maybe as much as half a billion dollars.

The first: Avatar, in all its 3D glory at the local cineplex. James Cameron spent at least $230 million – and maybe as much as half a billion dollars.

The second: Dr. Horrible’s Singalong Blog, a DVD gift from a hip brother to my 15-year-old. Dr. Horrible cost around $200,000 in up-front cash, maybe double that when you factor in all the donated services.Â

Yes, less than one-1,000th the cost of Avatar. (Put another way: Dr. Horrible cost less than six minutes of a mediocre hour-long scripted TV drama like Numb3rs.)

No, the point isn’t whether Avatar is 1,000 times more entertaining than Dr. Horrible. The point is that these two works are terrific in their own way; have vastly different economics; and are producing nice profits for their creators. Continue reading →