Entries Tagged 'Business of news' ↓

April 12th, 2010 — Business of news, Life, Technology and media

My favorite ballclub opens their brand-new stadium today, so forgive me if I seem a bit preoccupied.

My favorite ballclub opens their brand-new stadium today, so forgive me if I seem a bit preoccupied.

Watching all the hoopla – on multiple media platforms at once – gives us all another lesson on the folly of the paid-content argument from some traditionalists. Continue reading →

April 3rd, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics, Technology and media

Matt Mullenweg is at it again.

He’s the creator of WordPress, one of the free tools that’s reinventing the world of media and the very definition of what it means to be a “journalist.â€

How does Mullenweg justify giving away the results of years of work? Then working more untold hours on upgrades (helllll-ooooo Version 3!)? Then giving it away, too?

Simple: He builds complementary businesses that play in the WordPress eco-system.

You can set up your blog at WordPress.com for free. Want extra features – like truly massive amounts of storage for video, or a custom domain name? Pay a few bucks a year.

His company, Automattic, does other things, too. It provides hosting services for high-volume blogs. It builds paid add-ons for sites, like poll/ratings widgets. His latest is a service that makes it easy to create backups for WordPress sites – especially people who run large blog networks – for less than $20 a month.

None of these fees are large themselves, but they add up.

There’s a lesson there for journopreneurs:  Don’t get embroiled in the endless, economically unviable wishful thinking about paid content on the web. Relent and give the content away – then figure out how to make money elsewhere in the ecosystem.

That could be slick, intuitive and innovative delivery mechanisms – especially on tablets and mobile devices.

It could be building real communities around topic pages, comments and local blog networks, and serving as a sales-and-servicing agent for them. Or banding that community together for group-buying experiences.

Or – and this is the fun, scary part – it could be an idea that no one has figured out yet. One of just might.

(This is why one of my icons at Gravatar – another of Mullenweb’s companies – is a mad scientist. A small prize, and an AARP card, to the commenter who first identifies him. ;-) ).

(This is why one of my icons at Gravatar – another of Mullenweb’s companies – is a mad scientist. A small prize, and an AARP card, to the commenter who first identifies him. ;-) ).

March 26th, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism, Resources, Technology and media

Over at the GrowthSpur blog, Mark Potts and I have posted about a bunch of free tools we like that are highly useful for entrepreneurial journalists.

Over at the GrowthSpur blog, Mark Potts and I have posted about a bunch of free tools we like that are highly useful for entrepreneurial journalists.

(Oh – and that jokey lead about hardware stores? Not a joke. I’m so bad that the Fabulous Sue Corbett (trademark pending) jabbed me in a one-act play about Noah’s Ark she wrote for a youth group.

Scene: Noah’s sons talking after God commands their father to build an ark:

Son 1:Â You know what this means?

Son 2: Dad has to make a trip to the hardware store.

March 9th, 2010 — Business of news, Media economics

Hal Varian – brilliant economist, one of the few to apply the discipline to information, and all-round nice guy — got off a terrific blog post  at Google today.

I’d love to write extensively on it. But, as usual, Hal expresses his ideas far better than my pea brain can. In about 1,100 words, he manages to explain why paid content probably won’t work for most news sites; remind newsies that Google isn’t the enemy; and exhort news organizations to “experiment, experiment, experiment†for the civic good.

I know this won’t stop the incessant whinging from some quarters, or end the drumbeat of self-referential and circular thinking: “My work has value! Therefore someone should pay for it! So throw up a pay wall! Because my work has value!â€

For anyone willing to explore these topics with cool detachment, a couple more facts to give Hal’s work more weight. His Information Rules, written with Scott Shapiro, is a seminal book in the field of information economics (I’ve given away several dozen copies over the years, and it’s Book No. 1 in my personal essential bibliography of information economics). And odds are if you studied microeconomics in college, you read Hal’s work there, too.

Dismiss him as some sort of biased Googler at your own peril. This is one of the finest economic minds of our age.

A side note: I’ve heard some grumbling already about Hal’s assertion that very few advertisers are attracted to hard news.

I’ll go him one better, based on too many years of sitting in Monday-morning meetings where the previous week’s ad lineage results were discussed: About the only advertisers who insisted on being close to the hard news – in the A section, as far front as possible – were major regional and national advertisers like the department stores and cell-phone companies. Some wouldn’t even pay for the ad if they were bumped back to the Local section.

The rest of the advertisers? They didn’t care, or wanted to be far away from the news:

– Car ads (buried in the back of the classifieds sections, generally)

– Real estate ads (ever notice that they’re not in the Sunday real-estate or home section? Realtors hate news that isn’t “everything’s great! Buy a house!â€)

– Help-wanted ads

– Sunday free-standing inserts, tucked in the comics or some other pre-printed section

– Zoned retail ads in the Neighbors or hyperlocal sections

At most newspapers, those categories easily comprised 60 percent or more of advertising revenues in the halcyon days. Think about that: The majority of the money didn’t want to be near the news; they simply wanted the newspaper as a convenient delivery package.

February 11th, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism, Technology and media

Pete Townshend – yes, that greybeard who played at the Super Bowl the other night – has always been one of my favorite pithy writers. Don’t Get Fooled Again’s best line may be its last – “Meet the new boss/ Same as the old boss.â€

In this decade of unparalleled tumult at American newspapers, that cynical line could have been the motto for publishers. Sure, there’s been lots of talk about “dealing with change†and “transforming for a digital age.†But when it came time to hire their top editors, the new bosses have looked a lot like the old ones.

That’s why Thursday’s hiring of Jeff Light at the San Diego Union-Tribune was so refreshing.

I’ve never met Light, but I’m in serious envy of his resume: Most recently the VP of interactive at the Orange County Register. An MBA from Cal-Irvine. Impeccable Capital-J credentials as a member of the Register’s I-team (Pulitzer in ’96 for fertility-clinic fraud, a couple finalists as editor).

On paper, he’s the exemplar for the sort of digital journalists who are needed to rescue what’s left of the traditional industry. I wish him enormous success in a difficult job, and applaud the new owners of the U-T for moving boldly.

Sadly, there are still too few such bold appointments.  Let’s look at the top 40 U.S. newspapers by circulation. Since the beginning of 2008 – a time by which it was clear that the Good Old Days were gone, 10 of those shops have named a new top editor.

How many of those 10 came from digital roots?

By strict definition, precisely one – my former colleague, Debby Krenek, at Newsday. Debby’s previous role was managing editor – but she ran Newsday.com as well (and for all intents and purposes controlled big chunks of Newsday.com’s business operations too).

I’ve probably just offended any number of friends, so let me add quickly: Several more of the new editors have good digital instincts. Both Gerry Kern (Chicago Tribune) and Russ Stanton (L.A. Times) were closely involved with their shops’ digital initiatives (Russ even had the cool-but-inscrutable title of “innovation editorâ€). And my friend Monty Cook at Baltimore out-Twitters me exponentially. Â

But there’s still a difference between understanding it as part of your job and living it day to day as your entire job. Even if we give those three a mulligan, far too many of the other appointments smack of “stay the course.â€

Two of the “new 10†had previously been editors in chief at other newspapers, for example. Three others had been in a variety of editing roles at the shops they took over for 15 years or more (one for 27).

They may be terrific editors and decent people. But, symbolically, it’s hard to convince a newsroom that it must change dramatically when the top leaders haven’t been part of the digital groups that have to lead the change.

Don’t try, either, to argue that there just aren’t enough Jeff Lights out there. There’s been a significant brain drain in U.S. newspaper newsrooms in the past two years – and I’m not just talking about the layoffs of senior writers and editors.

You could populate a terrific news organizations with the digital editors who’ve left newspapers. In fact, that’s exactly what plenty of terrific news organizations have done.

There’s Kinsey Wilson, online editor at USAToday.com (and co-editor of the whole shop), who bailed to take over as senior VP and digital GM at NPR. Or Jim Brady, who banged his head against walls at the Washington Post for so long it’s a wonder he isn’t brain-dead (hmmm – might explain the Jets fixation) – and now is running Politico’s digital efforts (including their coming Washington local startup). Or Christine Montgomery, who left the St. Pete Times to become managing editor at PBS.org.

They’re among nearly a dozen high-ranking digital journalists who have left critical leadership roles inside U.S. newspapers in the past 18 months. Their landing spots? Start-ups, major portals, the reviving digital arms of public broadcasters.

So congratulations to Jeff, and kudos to his boss, Ed Moss.

To every other publisher, a question: Who is the best digital leader in your shop – and are you sure they were “out sick† that Friday a couple weeks ago?

February 4th, 2010 — Business of news, Media economics, Technology and media

Note: My friend and former colleague Bill Day is one of the sharpest sales-side guys I ever worked with. He’s adept at dealing with traditional, agency-driven advertisers and their massive buys – and maybe even better at bundling together innovative ideas like events, direct marketing and promotions to tap revenue from people who rarely advertise with local media. Bill has sold and serviced tens of millions of dollars in print ads – and quite a bit of online revenue for me, too.

He offers this guest post, from his seller’s perspective, on the publishing-industry frenzy over Apple’s iPad.

By Bill Day

Much is being made of the iPad as a vote of confidence from Apple for traditional publishers like The New York Times. Boosters point to the resurrection of the music industry on the backs of iTunes and the iPod. They predict a similar resurrection for publishers with the pending release of the iPad.Â

Poynter has an interesting take on the potential impact of the iPad on publisher subscription models here. It’s kind of like the cell phone loss-leader model – giving away flashy tech toys for long-term subscription revenue. It’s not a terrible idea. It just misses the point.Â

What’s lost in these discussions is a firm grasp of the mechanics of revenue generation for old-line media. As in “what’s the advertising model?†Continue reading →

January 30th, 2010 — Business of news, Technology and media

While I’m obsessed with digital media, the smarter part of my household focuses on the world of book publishing.

That world is agog this morning, because The World’s Largest Bookstore (registered trademark, etc.) yanked all the books published by the conglomerate MacMillan overnight.

The reason: MacMillan wants its ebooks to appear first on Apple’s iPad, not Kindle. Fine, said Amazon: We’re taking everything down then – hardcovers, paperbacks, Kindle editions.

The NYT and LAT has more details. This one will be fun to watch.

Unless, of course, you’re a MacMillan author. Ya think those screams you’re hearing from MacMillan’s authors were the intended outcome from Amazon? Why, I do too!

January 28th, 2010 — Business of news, Media economics

Much kerfuffle – and more derision than warranted – erupted earlier this week when the New York Observer reported that Newsday has sold only 35 online-access subscriptions since it walled off the site last October.

There was astonishment at the low numbers:

“Michael Amon, a social services reporter, asked for clarification. “I heard you say 35 people,” he said, from Newsday‘s auditorium in Melville. “Is that number correct?” [Publisher Terry] Jimenez nodded.

There was hand-wringing: The Observer’s John Koblin archly observed that Newsday.com’s relaunch and redesign last year cost $4 million … to gross $9,000 in revenue.

That analysis is technically correct, and utterly wrong. Ultimately, that’s why neither side in the Great Paywall Religious War should waste any time thinking about it.

Newsday’s pay wall isn’t about making online-subscription revenue. It’s only partially an attempt to protect print circulation. It’s all about protecting one of the most lucrative businesses around – high-speed Internet access.

The paywall rules first: The only people who get unfettered access to newsday.com are Newsday print subscribers (there’s the modest defense for print circ) and/or subscribers to the Optimum Online high-speed Internet service provided by Cablevision, Newsday’s owner.

Let’s do the math that the Observer, the grumblers in the Newsday newsroom, and just about every blogger out there didn’t bother to do. (I was hoping Alan Mutter would do it for me – lord knows he’s great at it – but he was writing about the iPad today.)

First, understand the economics of the cable-television business: Most of the costs are in stringing the wire past your house. (Lump in the copper or fiber itself, the equipment back at the cable headend and the labor to keep it all running.)

Depending on how tightly houses are packed, it all can run from a few hundred to as much as $1,500 “per household passed†in cable slang.

Oh – Cablevision pays that whether you subscribe or not. Every neighborhood they try to serve is a massive sunk cost.

Now let’s look at the revenue side of the cable business: A subscriber in my wife’s ancestral homeland of Massapequa might pay $50 a month for basic cable. But Cablevision has to share that revenue with the programmers – a few pennies per month per subscriber for niche channels like National Geographic, but more than $3 a month for behemoths like ESPN. Basic cable is a nice business, but not an obscene one.

The obscene ones are those the cable companies entered in the last decade: digital telephone service, and high-speed Internet. They had to upgrade their wiring – and for a company like Cablevision, that meant shelling out billions. But once they did, they could offer bundles of service with essentially zero added cost.

Think about that for a second: They already paid for the wires past your house. If they can get you to sign up, they collect $30 to $40 a month for high-speed Internet. Their cost? A few pennies in FCC fees (oh, wait – they add those onto your bill!), a few more pennies to print the bill (oh, wait – they’re bribing you to “go green!â€), maybe 40 bucks once for the cable modem (that’s why they give it to you!).

Let’s round it down and say that every Cablevision high-speed customer is worth $400 a year in profit.

That’s a fabulous business. Until, say, Verizon FiOS comes to town with a competitive product.

So the math gets really simple: If FiOs can convince a mere 100,000 people on Long Island to switch, Cablevision loses $40 million a year in profits.

If you’re Cablevision, you use every tool at your disposal to stop that. Even the blunt cudgel of a pay wall at Newsday.

I have no particular love for the spinmeisters at Cablevision, but the math backs up their words: the paywall strategy at Newsday is designed “to provide Cablevision’s high-speed Internet customers with reasons to remain with Cablevision, reasons to return to Cablevision, or reasons to choose Cablevision.â€

January 18th, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism, Media economics

A snarky comment on Alan Mutter’s blog set me off the other day. Alan was reacting to Mark Potts’ excellent riff on the coming iSlate (not just a fanboi dream, but potentially a great leap forward). Predictably, some of the commenters were pining for 1994:

“This smells a little like Google, which siphoned off $21 billion a year from newspapers without a squawk until publishers woke up.â€

We’ll leave aside the petty detail ($21 billion, yes. From newspapers? Um, no.) to focus on the bigger point. The real culprit in the Great Mass Media Collapse isn’t Google. It isn’t Craig Newmark. It isn’t the Original Sin of Not Charging for Content in 1994. (Alan, we tried. Remember AOL and Digital Cities?)

The real culprit? Gordon Moore.

The hero of our story

What, my journalistic brethren? You can’t quite recall studying him along with John Peter Zenger*, Thomas Jefferson & Woodstein back in J-school?

That’s because you almost certainly didn’t – but you almost certainly should now.

Moore, the co-founder and former chairman of Intel, observed in a 1965 trade-magazine article that the power of computing devices was doubling every two years. The importance wasn’t that electrical engineers could cram more circuits onto a chip – but that in doing so, the cost of computing would fall proportionately.

He theorized that the trend would continue indefinitely. Nearly 45 years later, it still holds – so much so that it isn’t called Moore’s theory, it’s called Moore’s Law. To a technologist, Moore’s Law is what the First Amendment is to us.

Want to know why you can get a DVD player for 29 bucks? Moore’s Law. Want to know how your cellphone has become so complicated you need a 15-year-old to explain it? Moore’s Law.

Want to know why newspapers are collapsing, or why local broadcast stations are becoming little more than a transmitter stick in an empty field? Then stop griping for a moment, and understand Moore’s Law.

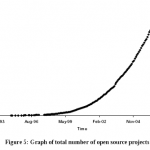

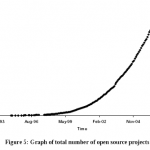

Exponential equations (doubling every two years) are tricky things to wrap your mind around. It’s not a straight line on a normal graph – it’s a hockey stick (or the right half of a parabola, to get all precise about it). To really get a feel for the numbers, you need to play with them.

The Official Chart of Silicon Valley

Dell.com has a spiffy, reasonably functional desktop computer this morning for less than $300. It runs at a speed – does things, in other words – that would have cost $600 in 2007, $1,200 in 2005.

OK, you say, got it: computers get better over time. But do you really get it? Keep going: The same performance would have cost nearly $20,000 10 years ago, at the height of the digital bubble. Not so long before that, when I was studying Zenger, Jefferson et al (and playing poker all night) in college, that much computing power would have cost nearly $5 million.

Here’s how that is “killing†newspapers: Let’s say you had an idea back at the top of the bubble in 1999 – a niche site for a community without a newspaper, or a portal of all the opinion pieces relevant to your city. You’d bring in a technology partner for a consultation. He says, “It’ll cost you a million bucks.†You’d probably gulp, and walk away. And, years later, you’d still be thinking “I can’t do that idea because it’ll cost a million bucks.â€

Meanwhile, some kid who understands Mr. Moore’s relentless math is chasing after that idea for under $30,000.

Therein are the roots of the woes affecting Old Media.

Our audience now has endless choices of news and information because you don’t need a $120 million printing press or a $50 million TV license anymore to publish. As Jay Rosen noted nearly four years ago, the people formerly known as the audience are now collaborators and potential competitors.

For the same reasons, our advertisers have the same sort of cheaper options. The local restaurant that used to buy a 2×5 coupon ad every week? Publishing their own coupons online, and laying our zero cash for a marketing program from Groupon. The car dealer? Using cars.com and AutoTrader for about $2,500 a month combined instead of buying a full-page ad for $10,000 a week.

Blaming Craigslist isn’t going to change those facts. Neither is blocking Google from crawling your site. (Notice how Rupert is screaming – but hasn’t actually blocked robots.txt yet?)

But “stop blaming the wrong people†is only half my intended message.

Why did we bother to study Zenger and Jefferson? Why are they considered heroes centuries later? Because of their spirits of daring, the possibilities they opened for us.

We should understand Moore’s Law now for precisely the same reasons. Yes, it has been a gigantic sledgehammer that has shattered the underlying business models of mass media, and it isn’t going to be repealed any time soon.

It also helps to remember that hammers are used to build things, too.

Instead of looking back, face the other direction. Pick up the hammer, and start thinking about what you can do with it.

Certainly that’s what my work is about these days. But I’ll pontificate some more about what kinds of things you can do with the hammer in a couple of days.

(*Colonial-era printer. Pissed off the governor of New York by daring to print criticism. Charged with seditious libel. Got off with the novel idea that truth is a defense. See, Bill Francois , I was paying attention.)

, I was paying attention.)

January 14th, 2010 — Business of news, Entrepreneurial journalism

The gang at GrowthSpur, of which I proudly call myself a member, is having another of its introductory sessions for hyperlocal and niche site operators.

We think journopreneurs – and people who just want to operate great local sites, whether or not they claim the “j” word – are one of the key parts of the emerging local information landscape. If you’re interested, drop a note to Mark Potts or to me.

My favorite ballclub opens their brand-new stadium today, so forgive me if I seem a bit preoccupied.

My favorite ballclub opens their brand-new stadium today, so forgive me if I seem a bit preoccupied.